Long-read sequencing - Part I

Next-generation sequencing. Source: https://www.bmglabtech.com/fileadmin/08_Blog/2019/next-generation-sequencing.jpg

Next-generation sequencing. Source: https://www.bmglabtech.com/fileadmin/08_Blog/2019/next-generation-sequencing.jpgDNA is unique to individuals (except for monozygotic twins), but some DNA sequences are shared between related individuals. DNA is the blueprint for all of our cells. Based on it, any cell can be reconstructed, and without it, cells cannot function. We can imagine DNA as a book written in a language we do not understand. We have only recently become able to read the letters written in this book, but we cannot make sense of most of what we read. Reading these letters is called ‘sequencing’.

Even though our understanding about how the DNA codes for life is limited, by comparing different DNA sequences, molecular biology has in the past twenty years revolutionized all of biology, providing useful information to practically all areas of biology. From evolutionary biology to behavioral studies, from medical diagnostics to food security, theoretical and applied branches have all benefited greatly from the technical breakthroughs of sequencing. I can only liken this genomic revolution to the spread of the microscope. Just as microscopy introduced us to a new world, the world of cells and microbes, sequencing has also brought previously unforeseen options to biology. And the same way that in the old days, wherever one turned the microscope, one could learn something new about the world, in whichever field of biology we apply sequencing, we make new discoveries.

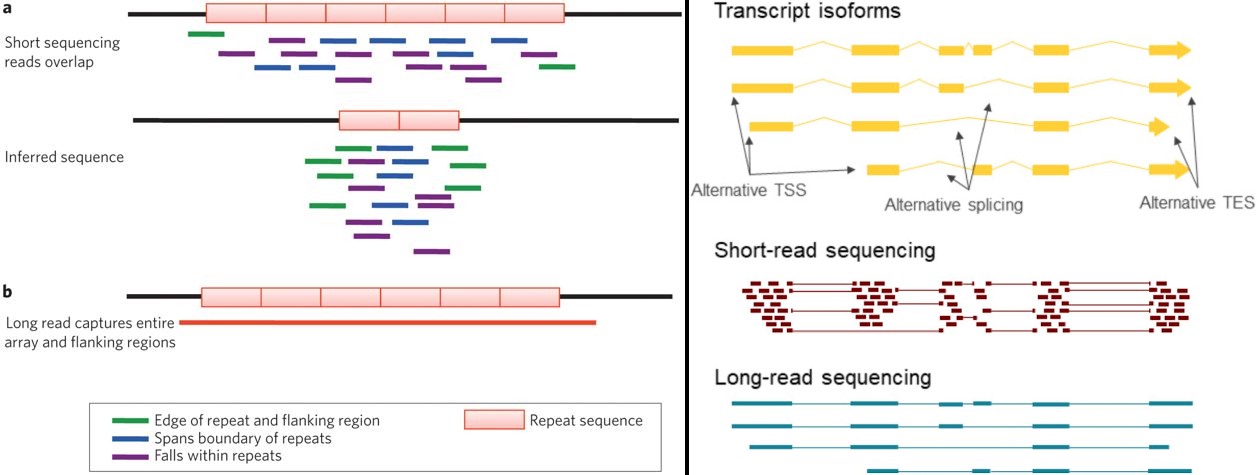

Fifty years ago, sequencing was a very slow and costly process. With the technology available at the time, sequencing a human genome would have taken many decades, costing billions of dollars. Next-generation sequencing technologies emerged about twenty years ago, and today, a human genome can be sequenced for a couple of hundred dollars in a matter of hours. This next-generation sequencing is based on reading short fragments of the DNA (short-read sequencing), which are subsequently assembled into longer fragments using high-performance computing. Next-generation sequencing is cheap, accurate and fast; however; it suffers from certain shortcomings. Long repetitive sequences are hard to discern, and connectivity between certain structures is hard to examine using short reads.

The third generation of sequencing is long-read sequencing. Next-generation sequencing significantly decreased the cost and the time expenditure of sequencing. The edge of long-read sequencing, in addition to this, is that it can sequence longer fragments of nucleic acids. This may not sound like a huge advantage at first because short reads can also be assembled into larger contiguous sequences computationally. However, DNA contains a lot of repeats, which make the assembly of short reads ambiguous (see figures). In these cases, long-read sequencing can provide extra information by precisely locating the origin of sequences. These advantages proved useful when assembling whole chromosomes and mapping highly repetitive regions or in RNA sequencing, because they can constitute full-length transcript isoforms, whereas isoform assembly, based on short-read sequencing data is challenging at best.

Long-read sequencing has clear benefits, but it also has drawbacks: for now, its higher error-rate and higher cost makes it a less attractive alternative to next-generation sequencing for most purposes. Therefore, long-read sequencing is gaining traction only slowly, achieving great successes in rather niche areas, while short-read sequencing still dominates general-purpose sequencing. In our next post on long-read sequencing, we are going to highlight areas where long-read sequencing has proven successful or is currently being applied frequently and we will also describe how our team utilizes long-read sequencing in cancer research.