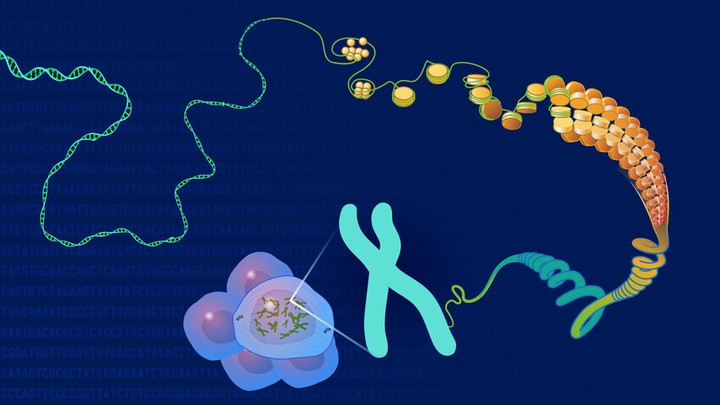

Genomics

In the last three decades, we determined the sequence of the entire human genome, developed computer-based methods for the analysis of genomes and developed new, cheaper, and faster sequencing technologies. Advances in genomics resulted in a million-fold drop in the cost of genome sequencing: it took 13 years and 2.7 billion dollars to sequence the first human genome and nowadays it takes only one day and roughly $1000. Consequently, genomic approaches today are more available, bringing remarkable advances in medicine, biological research, agriculture and forensics. However, genomics is still a relatively young field and public understanding of genomic technologies lags behind their fast-paced scientific progress. In the following I would like to showcase some examples to see how far we have come and what the latest breakthroughs are in the study of genomes — genomics.

Agriculture

In agriculture, genomics-based approaches enable farmers to accelerate and improve plant and animal breeding. The main goal is to select individuals with desirable traits, breed them and develop desirable characteristics in the next generations (selective breeding).

For example, even ancient farmers noticed that some plants may grow larger than others or some kernels tasted better. They saved kernels from plants with those desirable characteristics and planted them next year. Nowadays, advances in genetic research enabled us to identify which genes are responsible for traits of our interest, such as kernel taste and size. This information, coupled with technologies that modify genes can dramatically speed up the process of producing desirable varieties. The ability to change or introduce new genes in plants offered a new approach for fighting vitamin A deficiency that affects millions of people across Africa and Asia whose staple food is white rice (which is poor in micronutrients). The resulting genetically modified organism is known as golden rice, a rice strain with small genetic elements of corn and bacterial DNA which can synthesise a vitamin A precursor, beta carotene. In 2018, Canada and the United States approved golden rice for cultivation and in 2019, the Philippines authorised the direct use of golden rice in food and for processing.

COVID-19 pandemic

With the outbreak of COVID-19, genomics has shown to have an essential role in shaping the response to the pandemic. The SARS-CoV-2 genome was first sequenced by a Chinese virologist, professor Zhang Yongzhen, and his team and published on 11th January 2020. This enabled researchers to start developing diagnostics tests and vaccines.

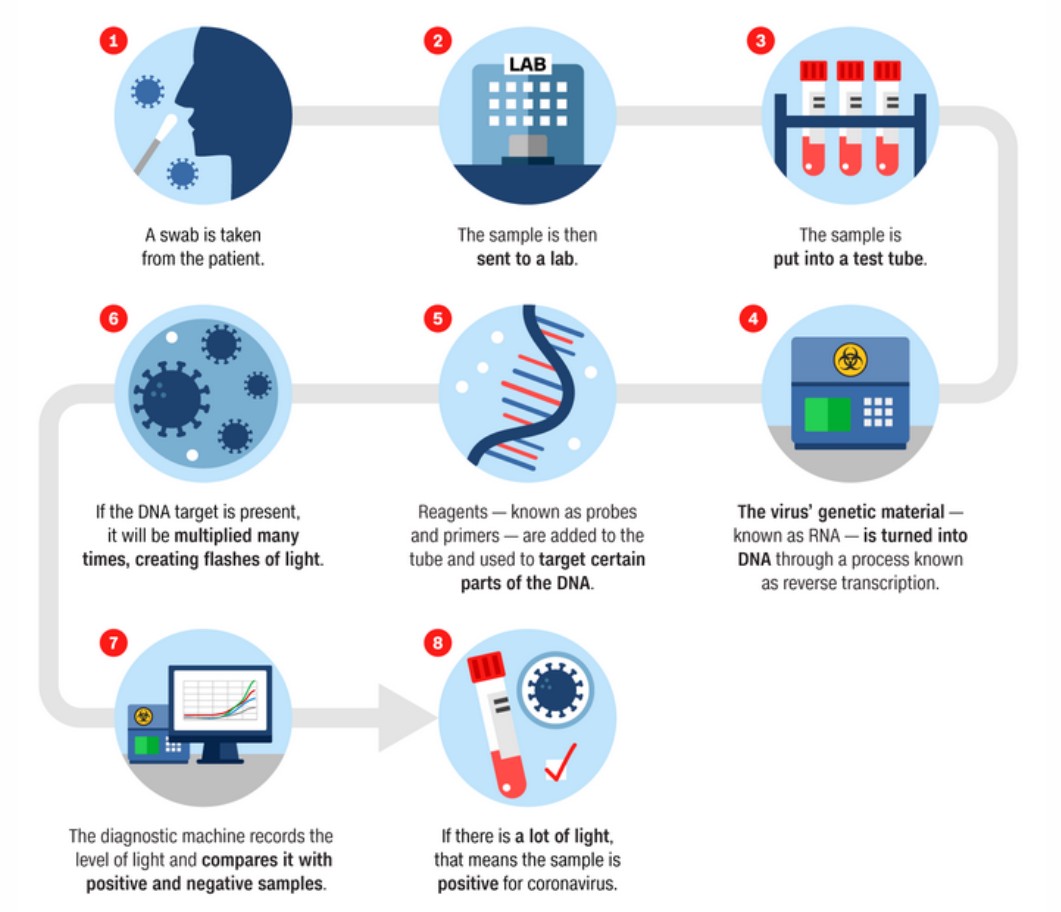

Identifying the genetic sequence was important for establishing the most accurate diagnostics test for detecting COVID-19, the PCR-based test on which the epidemiological surveillance relies greatly during the pandemic.

To develop a coronavirus PCR test, researchers identified the target parts of SARS-CoV-2 genome that were similar to the genome of the other SARS coronaviruses — parts that are less likely to mutate. Those parts are essential for the virus, providing it with the ability to replicate inside the host. If mutations in non-essential regions happen, the virus would still be able to live — invade the host and replicate. But if it happens in the essential region, the virus will most likely be disabled and mutation won’t be passed to the next generation. That way, the PCR test could accurately identify the virus even with mutations in its non-essential regions. The next step was synthesising short DNA fragments (targeting parts of the SARS-CoV-2 genome less likely to mutate) called probes that are fluorescently labeled. And simply put, if a person is infected with coronavirus, probes will bind to the fragments of the viral genome from their sample and the diagnostic machine will record this signal, giving a positive result.

Revealing the genome of SARS-CoV-2 also enabled researchers to identify the SARS-CoV-2 genome’s mutational rate (how often changes in the genetic information are passed to the next generation): 1-2 bases per month. With that knowledge, we can begin to understand how the virus is spreading because the genomic sequence looks a little different as the virus spreads and mutates among different populations and geographic areas. We could also use the genomic sequence to estimate the infected population size in locations with a limited scale of testing just by looking at the mutation rates.

This information could also help to identify superspreaders (individuals who infect unusually many others). According to Stern’s et al. analysis , 2-10% of individuals, superspreaders, were responsible for up to 80% of secondary infections. Analysing the mutation rates can identify superspreaders and tell which people were infected by them because those would have very few mutations as opposed to others — the same virus came from one person to many within few days, which didn’t leave enough time for it to mutate. Speed is an important part of this work. Therefore, researchers from Australia have recently published best practice guidelines and repurposed genomic sequencing capabilities to enable rapid analysis of a coronavirus genome in less than 4 hours. All it takes is to extract and analyse the SARS-CoV-2 genome from the swab of the diagnosed patient.

Cancer Genomics

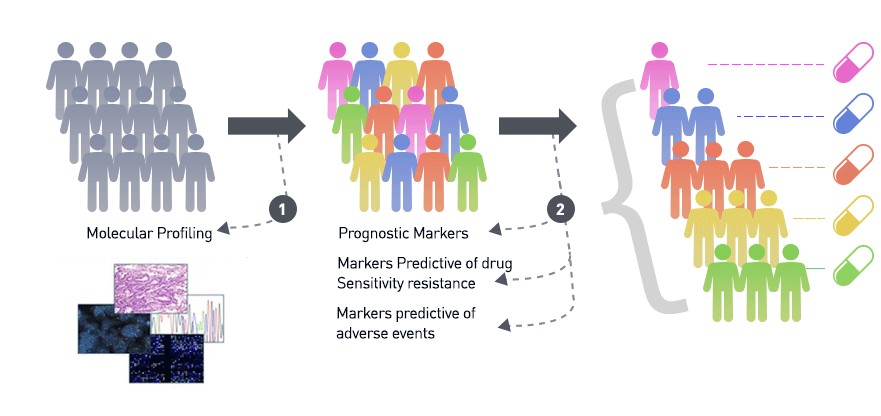

Recent progress in genome sequencing technologies also resulted in advances in treating cancer patients. Cancer is a disease caused by changes in the genome that alter cell behaviour, causing uncontrollable growth. These changes accumulate over one’s lifetime and are a consequence of environmental factors and inherited genetics. By sequencing the genome of cancerous cells and comparing it to genomes of healthy cells, researchers are able to identify changes that may cause cancer. Once these changes are identified, a better understanding of cancer growth, cancer type, and drug resistance can be gained by combining clinical data (e.g. response to treatment) and laboratory experiments.

By now, gene sets that often play a role in the development of particular cancer types have been identified. These genes carry information that can help to choose treatment strategies tailored to a patient’s cancer. Targeted therapies are designed to specifically combat characteristics of cancer cells that differ from normal cells. For example, in healthy cells, HER2 gene promotes cell growth and division. The products of these genes are located on the surface of the cell and can receive signals from the environment dictating the cell to divide at the right time. In some breast cancers, genomic changes may result in abnormal, accelerated cell growth due to HER2 being present in many copies resulting in too many receptors on the cell surface which then lead to uncontrolled growth. Targeted therapy for this type of cancer works by injecting a protein that would bind to the receptors and block the chemical signal that stimulates uncontrolled growth. That makes targeted therapies less toxic compared to other treatments such as chemotherapy or radiation that unspecifically kill both cancer and healthy cells. Gene sequencing panels are a powerful diagnostic tool and are now integrated into the clinical practice leading to better care of patients suffering from leukemia, breast cancer, and lung cancer.

I hope that with the above examples I managed to demonstrate the impact of genomics on our lives. This impact is only going to get bigger as genomics technologies continue to develop. Exciting times are ahead of us and I am looking forward to seeing what else genomics will bring to our world in the next decades and in what ways it will integrate with our lives even more.

Resources

15 Ways Genomics Influences Our World