Interpretable Machine Learning

Motivation

As machine learning (ML) models become increasingly used also in high-stake research domains such as healthcare, their adoption has been limited due to the difficulty of understanding the reasons underlying their predictions. Naturally, the research towards making the outputs of these “black-box” models less opaque has gained attention. This subdomain comes under many different names, interpretable ML or explainable artificial intelligence (XAI) being the most frequently seen. While the motivation behind making models explainable is rather clear, there isn’t always a consensus on the terminologies and approaches. This blog post is meant as a brief overview of the different vocabularies and explainability methods in healthcare and hopefully will alleviate some of the confusion surrounding the wide array of interpretability frameworks.

Definition

First of all, let us clarify the terminology that we will use throughout this post. While some do not agree with this$^1$, there seems to be a consensus to sacrifice a little bit of exactness for the sake of simplicity and therefore to use explainability and interpretability interchangeably.

Unsurprisingly, there is no rigorous mathematical definition of interpretability, but there are a variety of less restrictive definitions. For example, Miller$^2$ defines interpretability as the degree to which a human can understand the cause of a decision. Murdoch et al.$^3$describe interpretable machine learning slightly more precisely as the extraction of relevant knowledge from a machine-learning model concerning relationships either contained in data or learned by the model.

Frameworks

In a significant proportion of the literature, the explainability methods used vary with the researcher’s own opinion on what makes a “good” explanation$^4$. Furthermore, a major difficulty when developing interpretable methods, is that we often do not have access to a “ground truth” defining what makes a good explanation. This calls for particular caution since humans are naturally prone to confirmation bias and have a tendency to look for the explanations they expect.

From a technical point of view, the approaches can broadly be divided into two categories; model-based and post-hoc methods. Model-based methods refer to intrinsically explainable models while post-hoc methods aim to explain the results of a trained model. Some post-hoc methods are compatible with any model, in that case, they are also sometimes called model-agnostic. We describe below a few examples of interpretability frameworks and applications to ML models in healthcare.

Model-based interpretability

Intrinsic model explainability can cost some predictive performance. Indeed, the relationship between input and output is easier to understand in simpler models. A basic example is linear regression, in which the coefficient of a feature reflects the impact a change in this feature would have on the outcome. Linear models can easily be extended to generalized linear models (GLM) or generalized additive models (GAM) to take into account interactions or non-linear relationships between features and outcome. Unfortunately, as we increase the model complexity (and thus predictive performance) we lose the direct relationships between input and output variables and therefore entail a loss in interpretability.

Post-hoc interpretability

Post-hoc interpretability methods can be model-specific or model-agnostic. In both cases, they are applied only after complete training of the model and thus do not impact the performance. They are thus particularly useful in combination with more sophisticated models, that are not inherently interpretable.

Grad-CAM

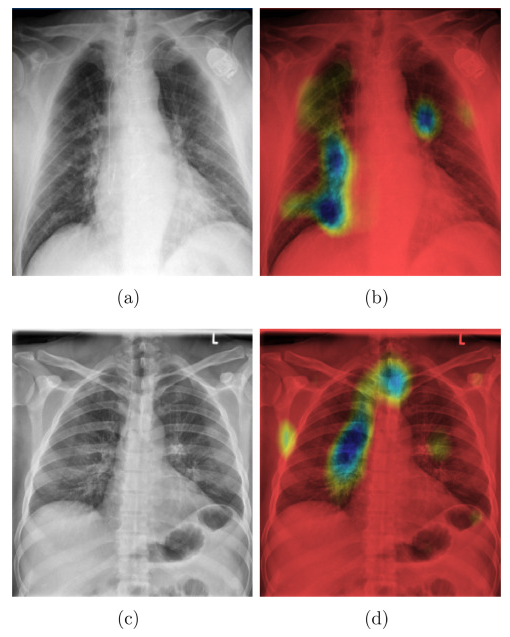

The Grad-CAM$^5$ algorithm is a model-specific interpretability method for Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs). CNNs have enabled breakthroughs in image recognition tasks, and have increasingly been used for X-ray analysis in healthcare. In image recognition, interpretability is often achieved by highlighting the important components of the input. The Grad-CAM algorithm achieves this by essentially computing the gradients of the predicted class with respect to the last convolution layer of the CNN and mapping them back to the input image.

Panwar et al.$^6$ developed a deep learning model using Grad-CAM to detect COVID from chest X-rays. These types of visual explanations are particularly useful for the validation of the model by domain experts (physicians). They can directly assess whether the selected parts of the input are indeed relevant for the diagnostic (Figure 1).

SHAP

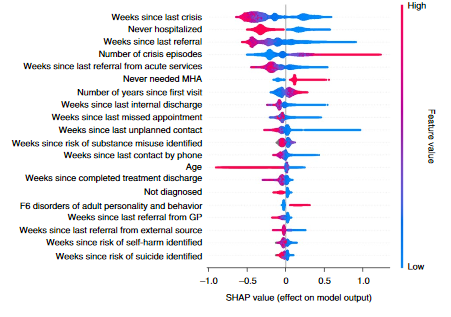

Shapley values are a concept coming from cooperative game theory, to compute how to fairly distribute a payout amongst players reflecting their contribution. In ML they can be used to compute the contribution of a specific feature to the outcome. Lundberg et al.$^7$ developed a framework combining Shapley values with other model-agnostic methods (e.g. LIME$^8$) to compute the Shapley values of any model. It is one of the most popular interpretability frameworks, because of its flexibility and ease of use.

Garriga et al.$^9$ implemented SHAP values to explain the predictions of an XGBoost$^{10}$ model used to predict mental health crises. The SHAP values show for example that the model predictions are negatively correlated with the number of weeks since the last visit and positively correlated with the number of crisis episodes. Shapley values are a powerful tool to assess how the feature values impact the model output and assess whether the model behaves reasonably.

Looking ahead

Nowadays, being explainable is one of the many requirements for a model to be deemed trustworthy. In April 2019, the European Union mandated an expert group to define a framework to achieve trustworthy AI. They published the Ethics Guidelines for Trustworthy AI$^{11}$, containing seven key requirements that ML models should meet to be considered trustworthy, in which explainability appears under the label transparency. This illustrates how rapidly new frameworks in AI need to be developed, sometimes even before having been rigorously defined.